Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 55, No.1 - Spring 2009

Editor of this issue: Gražina Slavėnas.

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 55, No.1 - Spring 2009 Editor of this issue: Gražina Slavėnas. |

Sąjūdis’s Peaceful Revolution, Part I

[This article continues in the next issue, Vol 55:2]

DARIUS FURMANAVIČIUS

Darius Furmonavičius, PhD in European Studies, University of Bradford, 2002, is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bradford and Director of the Lithuanian Research Centre in Nottingham. He is the author of Lithuania Rejoins Europe (East European Monographs and Columbia University Press, 2009).

Abstract

The article presents the internal factors that led to

Lithuania’s liberation. It analyzes the intellectual

leadership of Sąjūdis, which was able to steer the movement away from

Kremlin control and to exploit its mistakes in an effective way.

Sąjūdis’s successful political strategy was based on its

participation in two General Elections in Soviet Lithuania: to the

Supreme Soviet of the USSR and to the Supreme Soviet of the Republic.

Thus, Sąjūdis’s victories enabled the beginning of the

dismantling of Soviet power institutions in Lithuania, and became a

catalyst in the collapse of the Soviet Empire.

A generalized view of the revolutionary changes in the European political scene, which saw the collapse of what had long been discerned as the virtually impregnable Soviet system, might suggest that the changes that occurred in the Baltic States at that time were consequential to the processes of upheaval under way throughout Central Europe, and that the tactics of the Lithuanian leadership at this time were a mere reflection or localized expression of these broader processes. However, as John Hiden has sharply observed, “Gorbachev’s reforms occasioned rather than caused the remarkable contemporary reawakening of the Baltic republics,” and this suggests an alternative explanation.1 The truth is that the national awakening in all three Baltic countries, and in Lithuania in particular, was essentially proactive rather than reactive. It was clear from the first that the Lithuanians, as the closest neighbor of Poland and a nation that has shared much of its political history with the Poles, would take particular notice of Solidarność as that movement began to make its mark.2 In Lithuania, the general response to the perestroika process, therefore, quickly went beyond what Gorbachev intended to offer. Vytautas Vardys has observed that whereas Gorbachev sought “pluralistic socialism,” the Lithuanians moved forward subtly but decisively and sought a “pluralistic society” instead. They were encouraged in this by the recognition that this possibility was already being realized to a large extent in some former “Soviet Bloc” countries, like Poland, which had a westward-looking historical identity.3 This recognition was fundamental to Lithuanian aspirations. The ideological difference between the Soviet ”reformers” and the objectives of Sąjūdis lay in the implicit demands of the Lithuanian movement with respect to the questions of independence and the free market economy, which, in Lithuanian eyes, were essentially non-negotiable and inseparable.

While Gorbachev “in restructuring the economy, intended to introduce a degree of reform, Sąjūdis, like the other Baltic popular movements, […] made radical demands concerning private ownership and management.”4 Gorbachev proposed political reform, but the discussion of these changes necessarily proceeded “in a charged atmosphere of Lithuanian consciousness,” which was driven by more radical determinations.5 Many Western observers have argued that Gorbachev hoped to channel the energies of popular movements such as Sąjūdis into support for his own designs, but an inability to annex the mood of the Baltic populations to this ambition, and particularly to control the mass-movement processes in Lithuania, was to become his most striking failure.6 Indeed, it can be argued that his whole reform program eventually unraveled as a result. In this sense, the Lithuanian singing revolution can be seen as the essential catalytic element in the final destruction of the Soviet system, and it can reasonably be claimed that the actions of the Lithuanian people in support for Sąjūdis were instrumental to the Soviet collapse.

In many ways, the Lithuanian Atgimimas (Reawakening) beginning in 1988 can be defined in terms of increased public political activity on the part of its citizens directed towards the restoration of an independent state. International circumstances provided the background for this activity, particularly the increasing public awareness and the growing international recognition of the actual illegality, indeed criminality, of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact by which Lithuania and the other Baltic States, as well as eastern Poland, had been incorporated into the Soviet Union. Furthermore, the knowledge that the Western states had still not abandoned the policy of formal nonrecognition of the incorporation of the Baltic States into the Soviet Union now became a major encouragement in the growth of public political activity. In this atmosphere, Gorbachev’s announcement of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness) was seized upon as providing an opportunity to test how far the Soviet system was willing to change. The first public challenge to the regime was the commemoration in Vilnius of the anniversary of the secret Molotov-Ribbentrop pact on August 23, 1987, when the Lithuanian Freedom League arranged a gathering in Vilnius near the monument for Adomas Mickevičius, the great Lithuanian and Polish poet. Despite the announcement of changes in public policy toward demonstrations and open speech, the Soviet regime reverted to its characteristic form and persecuted the participants of the demonstration.

Celebrating Lithuania’s Independence Day, February 16, 1987, a dissident, Antanas Terleckas, reported to the Lithuanian Information Center in Washington about the attitudes of the Soviet state towards the public mood, testifying that people were “being intimidated in all kinds of ways. Students showing up will be expelled. Workers will be discharged.”7 The militia appeared in large numbers during the day on the streets of Kaunas, the former capital of independent Lithuania, and some of its members were seen accompanying well-known KGB officers, who were busy observing and filming the demonstration of a few hundred people marching through the Old Town and along the main street, which had by then recovered its prewar name of Laisvės Alėja, Freedom Avenue. Many in the crowd were prewar graduates of independent Lithuania’s gymnasiums in Kaunas and of Vytautas Magnus University. This anniversary of Lithuania’s independence was celebrated with great joy, conscious that this was being done in public for the first time in many years. For many families, it was also marked at home by listening to the radio, where they could hear the Voice of America or Radio Free Europe broadcast the speech given to mark the anniversary by the head of free Lithuania’s continuing diplomacy, Mr. Stasys Lozoraitis, Jr., Representative to the United States and to the Holy See. It was a memorable statement, and even today almost everybody in Lithuania who was interested in politics at that time can recall his optimistic speech, in which his belief in freedom, full democracy, and the independence of the country was unambiguously stated. His suggestions were, however, rather cautiously phrased, as he carefully weighed his words in the hope that his influence might encourage steps that could lead to the restoration of an independent state.

These developments signaled the beginning of real changes in the domestic atmosphere in Lithuania and in the international climate too, particularly in the United States. Thirty-two Senators, who had been concerned by reports of reprisals against participants during the demonstration in Lithuania, delivered a letter to the Soviet Embassy in Washington, D.C. on February 11, 1988, requesting that Mikhail Gorbachev should “act with restraint toward the Baltic peoples as they seek peacefully to express their aspirations for human rights and self-determination.”8 They expressed “concern about reports that the Soviets will move to block the flower-laying ceremonies at various historical sites in Lithuania’s two major cities, Vilnius and Kaunas,” and urged Gorbachev “to emulate the policy of Lenin, not Stalin,” in dealing with the Baltic States, “taking into account that the founder of the USSR renounced forever all Soviet claims to Baltic territory in 1920, a pledge that his successor violated two decades later.”9

This letter was one of the more important factors influencing the significant, but perhaps ultimately useful for Lithuania, overreaction of the Soviet authorities to the seventieth anniversary commemoration of Lithuania’s Independence planned for February 16, 1988. The Red Army troops were put into the streets in large numbers in advance, with the obvious intention of preventing people from gathering or demonstrating against the occupation of their country. This activity, however, produced the reverse of its desired effect, because the intensity of this Soviet reaction served only to focus the Lithuanian public’s attention on the actual meaning of the celebration. It encouraged them to take a greater interest in the history of Lithuania. The fact that this knowledge was still prohibited by the Soviet authorities also contributed greatly to the growth of international public attention and awareness of what was happening in the country. Indeed, it could be said that this obviously hostile military presence contributed its own confirming statement to the political environment, emphasizing everyone’s awareness of living in an occupied state. The resentment it engendered created an atmosphere that provided the conditions for the emergence of the new mass movement for Lithuania’s independence from the Soviet Union, namely Sąjūdis.

Despite the overreaction by the Soviet regime in 1988, it did not escape notice that this was, in fact, the first public commemoration of Lithuanian Independence Day to be held since 1940. Also, the enthusiasm with which it was embraced by the multitudes clearly indicated that the population’s fear of the Soviet regime had vanished. It is interesting to speculate why so many thousands of troops were deployed in the streets in response to a letter from thirty-two American Senators and why thousands of KGB and militia officers were so busy around the towns and cities observing the crowds, using cameras to film participants in a demonstration that had been arranged by only a few hundred of Lithuania’s independent intelligentsia. So obvious was this overreaction that many Lithuanians now began to sense intuitively that “something big was coming.”

Sąjūdis in Lithuanian means “movement.” Initially Sąjūdis was called Lietuvos persitvarkymo Sąjūdis (i.e., the Lithuanian Perestroika Movement), but later the word “perestroika” was dropped. Indeed, the early name was used for diplomatic and persuasive reasons only, because Sąjūdis had set itself the symbolic goal of a “free and independent country” from the beginning. In this, the Lithuanian movement differed from the Latvian and Estonian popular fronts, whose inception as intellectual movements of national reawakening and economic independence was much more closely marked by the support given by their communist elites to Gorbachev’s perestroika program.10 In Lithuania, the shape of the movement was different from the start. As early as September 1988, the famous Lithuanian poet Justinas Marcinkevičius had written an article which appeared on the front page of the first isssue of the Sąjūdis bulletin Atgimimas (“Rebirth”) stating that “the country that we inherited from our ancestors belongs to us. We call it Lithuania and we desire that this country shall not disappear from the map of the World.”11 Standing immediately beneath the title of the new newspaper, this message was a statement that the country must be born again. It was, therefore, a formulation that was profoundly at odds with everything the Communist Party had ever stood for and was a reflection of the core of the Sąjūdis movement.

Despite these profound undercurrents, it was necessary to prevent the Soviet system from demanding Sąjūdis’s extinction in the earliest days of its existence, and for the Iniciatyvinė grupė, the Founding Group of Sąjūdis, to secure its legitimacy within the process of perestroika in the Soviet Union. The majority of the members of this Founding Group were prominent intellectuals, and despite the fact that some of them were members of the Lithuanian Communist Party, Professor Vytautas Landsbergis was elected as its chairman. It was well-known that Landsbergis was not a member of the Communist Party. His selection was thus perceived as a means of steering the movement away from direct Soviet control. It was a clear signal of the strategy being unfolded. Landsbergis’s own description is evidence of the mindset of the movements’ leaders: “We called it ’Perestroika do konca,’ he explained – using the Russian phrase – which means “Restructuring until the end.” This implied “Restructuring until Lithuania’s victory,” i.e., until Lithuania’s liberation from the Soviet occupation was complete.12

The reasons behind Landsbergis’s election to this fateful position are worth exploring. It gave him the privilege of becoming the leader of the liberation movement and eventually the head of state who took his people through several crises and crucial negotiations and which finally, and probably against the expectation of many external observers, saw Lithuania becoming a free, independent, and sovereign state, and eventually a member of the United Nations and NATO. Landsbergis himself commented in an interview with the Lithuanian daily newspaper Lietuvos Aidas: “It is most likely that I was elected chairman because I was successful in settling quarrels between people with different views.”13 This is a modest response. Other opinions suggest that the repressive Soviet structures underestimated his ability for compromise, interpreting it as “softness.” They therefore failed to attack him effectively initially, even though this would have been well within their capability.14 Indeed, appearances were deceptive, and the Washington Post commented at the time: “Landsbergis is a soft-spoken professor of music at the Vilnius Conservatory where he specializes in early twentieth century avant-garde Lithuanian composers. His family is a mixture of old Lithuanian nobility and modern intellectuals. His father fought against the Bolsheviks and the Poles for independence in 1918, and the family helped to hide Jewish families during the Nazi occupation.”15 His earlier career had anticipated Sąjūdis’s goals, as it set out to restore an active appreciation of Lithuanian history to the nation’s academic life, and to free public life of the perverse interpretations which had become endemic during a half a century of deliberate Soviet falsification.16 Being a researcher of the works of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, the Lithuanian impressionist artist and composer, Vytautas Landsbergis succeeded in publicizing the works, thus preserving them from communist destruction and contributing to their recognition.17

The emergence of Sąjūdis encouraged many affiliated discussion clubs and societies to emerge throughout Lithuania, a feature of life that was all the more welcome for the fact that it would not have been tolerated in earlier decades.18 It is interesting to note how the Soviet authorities reacted in their characteristic attempt to ban the discussions of one of the more prominent of these societies, Istorija ir kultūra, the History and Culture Club, which had begun meeting at the premises of the Žinijos draugija, the Knowledge Society, in Vilnius. The club dealt with the threatened closure by simply relocating its discussions, moving into the hall of the Artists’ Union, where it carried on as before. Its discussions were influential, and during a meeting of the club held in April 1988, the philosopher Arvydas Juozaitis, who also happened to be an Olympic Medalist in swimming, read a courageous paper on the necessity of restoring Lithuania’s independence, which, naturally, was well-received.19 Similar intellectual discussions on the economic situation and the possibilities of independence took place between the economists who were members of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences. The group included Professors Kazimira Prunskienė, Kazimieras Antanavičius, Antanas Buračas and Eduardas Vilkas. Elsewhere, at the premises of the Cultural Foundation headed by Professor Česlovas Kudaba, other societies sprang into being that were concerned with the preservation of nature and the conservation of historic monuments. As a result, discussion began to develop freely outside the control of the communist authorities.

Sąjūdis naturally also aimed at reestablishing Lithuanian in its proper place in public life as the state language, and putting an end to the process of russification of public and academic life, which had been rampant since 1944. For example, from 1978 on, after the infamous Tashkent Conference, all doctoral dissertations had to be presented under the Soviet rules of candidature for higher degrees and written in Russian. The degrees were then confirmed by Moscow through Soviet institutions rather than by the universities within each Soviet republic. These language requirements, and the system within which the degrees were confirmed, caused particular anger in the Lithuanian academic community, as it did in Latvia and Estonia. To add insult to injury, the business of the Lithuanian Communist Party was conducted in Russian, which was the required language at all meetings of its Central Committee. Since nonparty members could not progress in their careers, this was another cause for anger. Thus, Sąjūdis’s aspiration to restore the nation’s language to its proper place had widespread support throughout professional circles. Indeed, the case for this restoration of its dignity was integral to Sąjūdis’s campaign to restore justice, and to respect the ability of Lithuanian people to decide how their lives and work should be conducted. The language question became a reflection of people’s attitudes toward moral values in the context of the feeling, endemic in Soviet times, that the moral values of public life had been lost. It had become a habit to do one thing, to say something else, and to think one’s thoughts in secret. Plagiarism, false statistics, evasion, theft, and denunciation had in fact become the norm throughout Soviet society, while duplicity and deception were, in the same vein, common in municipal and public life. Neither personal autonomy nor individual opinion was much respected by the Soviet system, if people held views that differed in any way from those demanded by officialdom. These difficulties had caused major problems that would have to be overcome in the new society, which Sąjūdis hoped would develop when the Soviet communist dream had exhausted itself.

Sąjūdis also set out to encourage a deep respect for nature and the environment. It called loudly for a cleanup of the polluted rivers and landscapes that could be found in many places throughout Lithuania, where the ruthlessly exploitative industrial process of the command economy had damaged the environment without putting anything back. Many rivers were nearly devoid of life due to the absence of measures to clean up pollution, and much of the soil was badly affected by the excessive use of artificial fertilizers or was contaminated by the chemical industry in such places as the fertilizer factories at Kėdainiai and Jonava. The worst case was the Chernobyl-type atomic energy power station at Ignalina, one of the most powerful stations in Europe. It played an important role in Soviet nuclear defense plans, with two reactors built in the lake district of a national park. Open discussion of these problems and firm 15 opposition to these matters were the basis for the broad public support that emerged for Sąjūdis’s environmental policy. Eventually, the birth of a Green Party, Žaliųjų partija, succeeded in stopping the Kremlin from building a third nuclear reactor at Ignalina, as well as the construction of the Kaišiadorių hydro-accumulative power station, which threatened the existence of life in Kauno marios, the great artificial lake which lies on the Nemunas river near Kaunas.

The key words of the Sąjūdis movement, often repeated, were “honesty,” “wisdom,” and “spirituality.” Indeed, the movement campaigned openly for the spiritual revival of the people and for a better and more honest way of life.20 Sąjūdis was, therefore, responsible for introducing the policy of public moral integrity, which suggested that the political culture should be based on Christian principles. It was a stance that radically distinguished its activities from the existing Soviet outlook, which was based on the fear of persecution. This commitment by the intellectual elite of the Sąjūdis movement inspired people to throw off the profound fear that had gripped the entire country since the Stalinist period. It was accomplished through personal example and the personal risk of gathering together. The technique won because it opened hearts. In this way, Sąjūdis aroused public enthusiasm for the restoration of Lithuanian independence based on an understanding of democratic values, embracing the vision of a restored state, a parliamentary republic, and true independence from the Soviet Union to be achieved by means of the ballot box. 21 This vision was grounded on a call for historical justice. It suggested that the Soviet-Nazi agreement, which had divided Europe into zones of influence reflecting Stalin and Hitler’s position that all small states would have to disappear in the future, was at last to be annulled. Thus, the resulting illegal occupation of Lithuania by the Soviet Union would have to end.22 Sąjūdis’s civilized understanding of the need for the peaceful expression of ideas stood in sharp contrast to the brutality of the totalitarian regime. At first, it offered a challenge the system felt it could assimilate, but eventually its moral force was such that the regime was unable to ignore the large-scale peaceful demonstrations and gatherings of Sąjūdis. The movement’s emphasis on a “cool, calm, and coherent” disposition held firm, even when faced by the brutal power of Soviet state institutions, including the KGB. In the face of provocations, the movement turned to the example of Gandhi and other cases of peaceful liberation and nonviolent resistance. At times this was directly articulated by Landsbergis, who was one of the most intellectual and well-read of the leaders.23 In the final analysis, it was this method that saw the Soviet Russian intruders off Lithuanian territory, as surely as the British Raj was seen out of India half a century earlier, though the Soviet communist occupier was much more brutal and much more reluctant to leave.

We need to recall at this point how Lithuania’s Sąjūdis movement first materialized in the summer of 1988, under some inspiration derived from the emergence of the Estonian National Front, which took advantage of a distinct relaxation of the communist regime in the occupied Baltic States. Sąjūdis actually came into being on June 3, 1988, at a time when public life was dominated by discussions about the drafting of a new constitution for Soviet Lithuania and a plan for the country’s future economic development. The occasion was a meeting in the Small Conference Hall of Lithuania’s Academy of Sciences.24 Only a day earlier, a monthly discussion on the situation in the country, organized by Professor Bronius Genzelis, had taken place in Mokslininkų rūmai, the Palace of Scholars, in the village of Verkiai in the Vilnius region. The participants in that discussion, recognizing the significance of the moment, formally resolved to redesignate the following day’s session as a broader national meeting to discuss the country’s future systematically. This meeting then became, without any real previous planning, the effective founding meeting of Sąjūdis, since participants then went on to elect the Iniciatyvinė grupė, (Founding Group) for Sąjūdis, which embraced the most prominent intellectual figures present, representatives of the nation’s cultural and scholarly organizations and institutions.25 The hope was expressed at this first meeting that these people “could unite those institutions and raise foundations for the new and powerful movement able to take responsibility for the restoration of Lithuania’s independence.”

Professor Vytautas Landsbergis has recalled the significance of that day in his interview for the BBC documentary film “The Second Russian Revolution”:

The most important moment was when we were elected. I wasn’t there, but the next day I was told that the Committee had been elected and that I was on it. I was at that meeting at the beginning, but then had to speak on television. There I said that the movement should be created, we shouldn’t wait any longer; we are already late. Even the first meeting of the group went off without me; I wasn’t informed in time. After that I was at every meeting of the committee. They were quite unusual; there were also meetings with the people, they lasted for many hours in stuffy rooms, but nobody cared. There we formulated ideas that were to become a program of action and our methods.26

The fact that the Estonians had moved earlier to create a popular front undoubtedly gave an impulse to the Lithuanians at this stage. When the Estonian Popular Front was established in May 1988, Arvydas Juozaitis participated in its inaugural meeting as a representative of Lithuania’s emerging movement for independence.27 Later in the month, the prominent Estonian economists Mikhail Bronstein and Ivar Raig visited Lithuania on May 26–27, 1988, to describe the political developments in their country. They were the acknowledged authors of Estonia’s economic independence and had explained the constitution of their recently established Estonian Popular Front and its program to the members of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences. The reaction was enthusiastically positive, and it was agreed that a similar movement must emerge in Lithuania as soon as possible.28 The meeting chaired by Professor Bronius Genzelis on June 2 led directly to the founding of Sąjūdis on June 3, and it is interesting to note that Lithuanian physicists were the instigators and among the most active supporters of the emerging new political processes.29

These leading scholars were well known both for their scientific work and for their critical thinking about the Soviet system. The Empire had tolerated them despite their humorous deprecation of its workings, probably because the majority of them were connected with research contracts for the Soviet military industry. They were a sophisticated constituency and their tactics were subtle. One of their ploys was to challenge the Central Committee of the Communist Party in Lithuania by producing an “informal” list of candidates to the Communist Party conference in Moscow. The list, purporting to be in support of Gorbachev’s attempts at perestroika, was published on May 27, 1988 in a Vilnius newspaper, Vakarinės naujienos, by members of the Academy of Sciences Institute of Semiconductor Physics.30 The move was a masterstroke, conceived by well-honed minds, and the Central Committee of the Communist Party in occupied Lithuania was really cornered by this carefully considered tactic. It was a maneuver which faced the Central Committee with a major dilemma, because now they had to either accept the physicists’ proposal, which required following Gorbachev’s public instruction that candidates to the conference had to be elected by secret ballot by Communist Party members in various organizations, or continue with its habitual method of nominating its own candidates without reference to any wider consultations. If the first path was followed, it was now obvious that the mood of the country was such that the Central Committee’s nominees were very likely to lose the elections. Alternatively, the Central Committee could neglect Gorbachev’s instructions and send its own candidates to Moscow without holding elections. It was, of course, unable to change its corrupt habits, so its response was to adopt the latter course, following a pattern of behavior which had become second nature to its members. But they had been smoked out, and the fact that the Central Committee of the Communist Party had ignored the list of candidates provided by the physicists of the Lithuanian Academy of Science exposed it to public opinion. Thus, immediate charges of flagrant abuse of the electoral process were loudly voiced. The Party had, of course, been indulging in such cynical manipulation for ages, but now it was seriously stung by a vigorous public outcry directed against its unseemly behavior.

These developments in the nomination of candidates for the All-Union Conference of the Communist Party in Moscow marked a critical stage in the change of popular attitudes. The reaction of the Central Committee of the Lithuanian Communist Party damaged its reputation not only in Lithuania, but also in the Kremlin, as it demonstrated its inability to react effectively to the challenges of contemporary society, and showed its incompetence “to play the perestroika game” in occupied Lithuania. From the viewpoint of Sąjūdis, this was the first successful step in discrediting the Central Committee of the Communist Party in Lithuania. It was a significant boost to its self-confidence, and it suggested that the best tactics were ones of “push and wait.” This policy meant that the movement would be well advised to make radical demands and then simply wait for the Communist Party leadership to make a mistake. It would then be advertised widely in a manner that would further discredit the communists in the public eye.31

Almost as soon as it was established, the Sąjūdis movement began to lay out a program for national reconstruction that was virtually an election program for an alternative government. When the first public meeting of the Founding Group took place on June 13 , 19 88, it was announced that commissions would be established to investigate national ecological, social, economic, cultural, and legal issues, as well as the “national question” itself. The records of this first meeting reflect an impressive unanimity of purpose.32 Sąjūdis established its own news bulletin Sąjūdžio žinios (“Sąjūdis News”), which was produced without the approval of Soviet censorship. Its own duplicating machine was used for the earlier copies, though later it was distributed and multiplied by the various local Sąjūdis groups. Then Sąjūdis information boards also sprang up in the towns and in the offices of various organizations. Soon an independent press began to flourish. Atgimimas (“Rebirth”) appeared weekly in Vilnius; Kauno aidas (“The Kaunas Echo”) in Kaunas; Mažoji Lietuva (“Lithuania Minor”) in Klaipėda, while other periodicals followed in many other towns. The most important achievement, however, was Sąjūdis’s success in gaining access to the republic’s television with the establishment of a one hour program Atgimimo banga (“the Wave of Reawakening”), which soon became the most influential and popular TV program, not least because Sąjūdis was able to ensure that its major meetings, demonstrations, and gatherings were reported live, or recorded to be shown to the Lithuanian people on this program. With this energetic publicity drive, Sąjūdis was able to educate the public, and began to achieve significant results within a few months of its establishment.

The progress of the movement was rapid, and its momentum astonishing. Osvaldas Balakauskas, a professional composer and member of Sąjūdis’s Founding Group, who was subsequently appointed Lithuanian Ambassador to France, has described the year 1988 in the following terms:

There was a quiet start between January and May, while the establishment of Sąjūdis was being worked at. The first of three large meetings took place in June. The second meeting was in July; and the third, which was the first high point of its activity, was held in August. The reaction, and the strengthening of the revolution occurred in September, but the highest point of the year came with the General Meeting of Sąjūdis representatives in October. After experiencing its first defeat in November, the ”political advent” then followed in December.33

This rather sparse overview describes the stages in the growth of Sąjūdis’s political strength during its first year of existence rather well, but the comments of Vaclovas Aliulis, MIC, a Marian Priest and another member of the Founding Group, on the major achievements of 1988 are needed to fill out the picture. In his opinion, the general public, particularly the younger generation, became fully aware of the truth about the current situation and the real facts of the recent history of Lithuania only after details about the numbers of innocent people who had been deported to Siberia between 19 41 and 19 52 were brought into public view. Further, as Lithuanian was given the status of the republic’s language, the will of the nation for independence from the Soviet Union became more clearly expressed. These developments were eventually to become firmly focused by the national petition drive in the summer of 1989, which protested against Soviet constitutional amendments that limited the rights of republics to secede from the USSR. In the space of a single week, Sąjūdis was able to collect 1,650,000 signatures from a total population of nearly four million.34

|

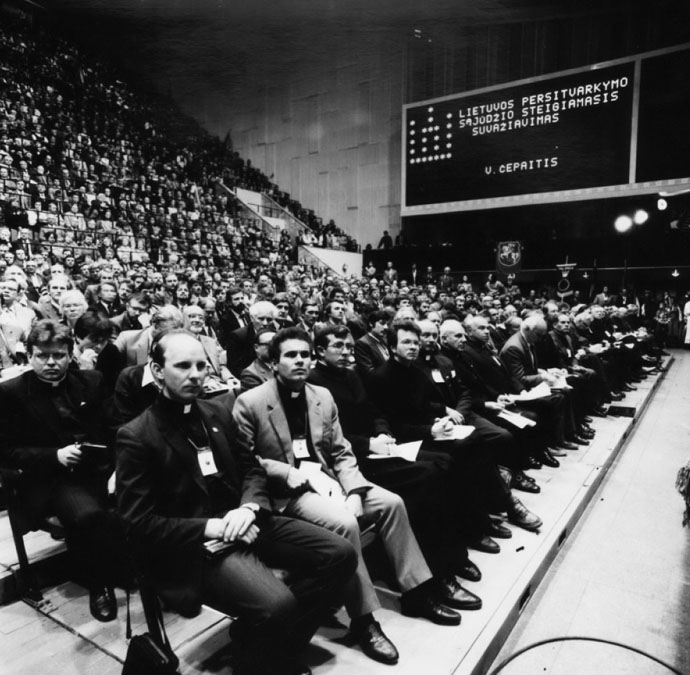

| The

Founding Group of Sąjūdis Conference in Vilnius on October 22, 1988. |

The strategy of the movement was already embodied in embryonic form in the statement (made at the first general meeting of its representatives held on October 22, 1988) that its objective was to employ “all constitutional means of struggle for Lithuania’s sovereignty."35 The formulation of seeking a “constitutional way for the restoration of the Lithuanian state” was proposed by the Kaunas Sąjūdis group, which was more radical in its views at that stage than the branches in Vilnius and elsewhere.36 Shortly after this, Vytautas Landsbergis’s formula “what was stolen, must be returned” emerged following his discussions with Stasys Lozoraitis, Lithuanian Ambassador to Washington, and Dr. Bill Hough, an expert on International Law in New York.37 It became a slogan of some genius in this context, because the simplicity of its understatement was compelling enough to bring those who might otherwise have wavered into line with the Kaunas group’s formulation. Sentiments on the constitutional nature of the struggle, and the realization that its goal was the hope for return of stolen independence, were fused to become an unequivocal demand and a nonnegotiable reality.38 Lithuanians would henceforth emphasize at every possible opportunity that they had never joined the Soviet Union freely and were in fact the victims of the secret Soviet-Nazi pact. They used the moral force of this argument as a wedge with which to split the Soviet system, exploiting the opportunities offered by both the western policy of nonrecognition and the right of a Soviet republic to withdraw from the Union under the Constitution of the USSR. When the implications of its defined position were fully absorbed, Sąjūdis then declared that it is “not we who should withdraw from the Union but the Soviets who must withdraw from Lithuania, because we never entered it of our own free will.”39

In this situation even the activists of Sąjūdis felt the best way to restore Lithuania’s independence was evolutionary rather than revolutionary. They knew that, according to the Soviet Constitution, any republic could (at least in theory) withdraw from the Soviet Union. They were also aware that, despite this formal position, the Communist Party and the KGB both existed to guarantee Soviet unity. It is interesting to note in this respect that when a two-and-a-half-hour discussion took place on August 31, 1988, between the Sąjūdis leaders and General Eduardas Eismuntas, the head of the KGB in Lithuania, and Edmundas Baltin, his deputy, the question of the constitutional right of the Lithuanian Soviet Republic to withdraw from the Soviet Union was both raised and admitted.40 In reality, however, the Communist Party regarded it as its prime duty to ensure that the republic would never exercise that right, and General Eismuntas confirmed this fact in the same discussion by telling the Sąjūdis leaders:

If you wish to leave the Soviet Union by implementing this constitutional right, and if you use the slogan that you wish to exploit your constitutional right to leave the Soviet Union, I will have no objections, nor will anybody else. That is your constitutional right. You can exercise it, please, but […] as a communist, I will fight for Soviet Lithuania, for the socialist system, and for Soviet Lithuania to remain within the Soviet Union.41

To publicize its goals, Sąjūdis organized public meetings and demonstrations. A number of smaller demonstrations on the environment, all of them peaceful, took place near controversial industrial enterprises. Many were opposed to the construction of a third reactor at the Chernobyl-type nuclear power station at Ignalina, the largest of its type in Europe. Many demanded a reduction in the scale of the hydro-accumulative power station at Kaišiadorys, and intensified their protests against a whole series of highly-polluting Soviet chemical factories.42 It is also important to record that the ruling elite also attempted to resist further environmental pollution of the country by the Soviet chemical industry. The environmentalist Česlovas Kudaba was prominent in his attempts to attract local and international public attention to problems of pollution from chemical plants, as well as other issues, such as excessive land-drainage schemes that were destroying the natural beauty of Lithuania’s landscape. These consistent protests struck a deep chord in the Lithuanian community. The political scientist Vytautas Vardys has rightly said: “Moscow’s insistence on further expanding Lithuania’s chemical industries was a major factor in uniting the communist intellectual elite in their support for […] Sąjūdis in the summer of 1988.”43

WORKS CITED

Ash, Timothy Garton. We the People: the Revolution of ‘89 Witnessed in Warsaw, Budapest, Berlin and Prague. Cambridge: Granta Books, 1989.